To begin a discussion on the digital revolution in the humanities, we asked some questions to our scientific advisors. Their answers will be published in eight issues between now and mid-October. Here, as a second issue, those of Peter Burke and Elisabetta Benigni.

Index

I) Agnese Accattoli and Davide Bondì.

III

Peter Burke

What generation do you feel you belong to?

The Generation of 1956, marked by two crises, one in Suez and the other in Hungary, encouraging a critical approach to both the British Empire and the USSR and proving Karl Mannheim right about generations as constructed by the experience of major events.

How and when – in your personal experience – did the digital revolution happen?

Slowly – I did buy my first Mac in 1985, but avoided e-mail till I retired in 2004 (afraid of being overwhelmed by messages from students) and I still keep well away from Facebook and other social media. The best thing for me is the digitization of articles and their availability thanks to JSTOR.

Is the “old” way of working still present in your life? (for example: do you write by hand? do you use paper archives that you keep in order? do you usually read in the library?)

I still take notes on and in books by hand and transfer them to my computer later. I still have and consult a card-index of books and articles, but I have not kept it up to date since 1990 or earlier. I like to work in libraries.

What do you think about the “digital” organization of scientific-cultural work? To what extent would you define the current way of working as new?

I do not know about other scholars’ way of working. I like to capture and download images from the Internet to illustrate lectures and books. I use Wikipedia to save time when I need to check a fact while writing a paragraph, but if the information is important for me I will check it later. Conversing with scholars all over the world by e-mail is a boon!

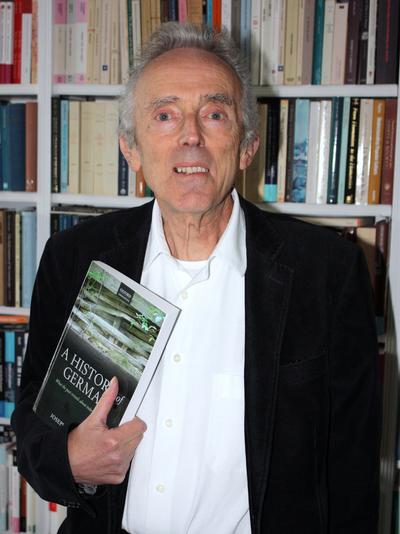

Peter Burke, Emeritus Professor at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, an internationally renowned maestro of historical studies, works on cultural history, including popular culture, and the history of knowledge, from the modern age onward, in a comparative history perspective that exploits a rich variety of evidence.

IV

Elisabetta Benigni

What generation do you feel you belong to?

A middle generation, among those of my teachers, for whom the transition to digital happened very late, in an advanced phase of their lives after they had worked for years following the old pen-pen-writing machine model and the generation just after mine that was, so to speak, born digital and has a very close, daily relationship with technology since childhood.

How and when did – in your personal experience – the digital revolution happen?

It happened during my university years. Having done classical high school, moreover in a provincial city, the digital world was forbidden to me. I arrived at university with a vague and confused idea of the benefits of using digital technology in my studies and during the first years of university I used the computer discontinuously. I simply did not consider it an essential resource in the construction of my cultural background, as books were. Only during the writing of my thesis I started to write all the text on the computer and to use many online resources. It was my first constant use of a digital medium.

Is the “old” way of working still present in your life? (for example: do you write by hand? do you use paper archives that you keep in order? do you usually read in the library?)

Yes, absolutely. I find it very hard, as for many people, to read everything on the screen. I go to the library, I read magazines, sector or not, in paper, I take notes in pen, even in pencil, of what I read and I keep archives of notes in notebooks catalogued in a precise way. I must admit that, as I travel a lot, sometimes I regret my obsession with paper.

What do you think about the “digital” organization of scientific-cultural work? To what extent would you define the current way of working as new?

In many ways I believe that in the way we do research it is not a really radical revolution. After all, in the way we work, the screen has replaced the paper and the keyboard has replaced the pen. Digital archives have replaced paper archives, but are they really so different? I don’t think so. In general, I find digital resources better organized and easier to consult than paper ones. The radical change is found, instead, in the transmission of knowledge, in the way we teach. Teaching through a digital platform has some positive and negative aspects but it undoubtedly creates a radical break with the old master/student relationship. It puts to the test a certain category of teachers, university and school teachers, who had marked their way of teaching according to a narcissistic model of empty lessons, with little content, a lot of disorder and ramblings. These ramblings of the worst kind, however, did not inspire or even nourish creativity. The digital forces to synthesis, to know what one is looking for and how to do it, to speak less and more strictly. On the other hand, one risks turning lessons into empty and depersonalizing containers. The absence of a physical referent, i.e. of looks and bodies, is an aspect that affects a lesson very much, negatively of course. I have recently completed my online courses and I have noticed that the emotional investment in these lessons has been very low. Few disappointments, few satisfactions, few “return” feelings. If it was like that for me I imagine it was the same for my students.

Elisabetta Benigni is an assistant professor of Arabic language and literature at the University of Turin. Her research focuses on comparative literature in the Mediterranean context (transmission of texts, translations and cross-influence), prison and resistance literature, literary translations and translation studies, and early Modern and modern contacts between Italian and Arabic.